Climate and Human Rights

Foreword

This report is an updated and revised English version of the report “Klima og menneskerettigheter”, published by the Norwegian Institution for Human Rights (NIM) in October 2020. Chapter 4 on Section 112 of the Norwegian Constitution has been revised to reflect the interpretations adopted by the Norwegian Supreme Court in a plenary judgement of December 22nd, 2020. This chapter, along with other parts of the report pertaining to national law, have been significantly shortened for the benefit of international readers. Chapter 5 on the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) has been updated, to reflect new developments in national jurisprudence across Europe and recently communicated climate cases before the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg. Chapters 8 and 9 on climate displaced persons and international climate cases have also been updated, to account for new developments in the area.

Abbreviations

- ECHR

- European Convention on Human Rights

- ECtHR

- European Court of Human Rights

- IPCC

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- ICCPR

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

- UNFCCC

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

- ICESCR

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- CO2

- Carbon dioxide

Summary

Who is NIM?

The Norwegian National Human Rights Institution (Norges institusjon for menneskerettigheter, NIM) is an independent public body established by the Norwegian Parliament to strengthen and protect human rights in accordance with the Constitution, the Human Rights Act and international human rights law.

What is the link between climate and human rights?

Climate change is the greatest threat to the realisation of human rights, according to the UN High Commissionar for Human Rights. The most fundamental link between climate change and human rights relates to the commitment to prevent further climate change from occurring. Human rights may also require States to adapt to climate change, and to undertake specific assessments when it comes to certain climate actions. The theme of this report is the commitment to prevent further climate change.

What scientific premises are NIM’s assessments based on?

NIM has commissioned the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research Oslo (CICERO) to clarify the link between greenhouse gas emissions and climate risk. CICERO describes how temperatures have been greatly altered by human activity compared to natural variability in most places. Continued climate impact, especially from CO2 accumulating in the atmosphere and thereby causing further warming in both the short and long term, immediately contributes to exacerbating many types of climate risks. Climate risk is generally considered to increase in step with global warming and is, for instance, significantly greater at 2 degrees than at 1.5 degrees. Climate change is already contributing to an increase in many types of climate risk, for both nature, society and people. Further emissions, including from Norway, will intensify this risk, both locally and globally.

Does Section 112 of the Constitution grant climate rights?

Section 112 of the Constitution determines that everyone has a right to a healthy environment and an environment in which productivity and diversity is preserved. According to a recent Supreme Court judgement,1HR-2020-2472-P. these rights apply not only in relation to the environment, but also in relation to climate. The provision encompasses exported greenhouse gas emissions from Norwegian oil and gas production. The protection under Section 112 is both of a substantive and a procedural nature. The Supreme Court confirmed that both the substantive and the procedural rights are justicable. However, there will be a high threshold for overruling decisions that affect substantive rights, when these decisions were made by or with the consent of the Parlimement.

Does the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) establish a duty to avert climate change?

Environment in ECtHR practice. The ECHR does not include an explicit right to a clean and quiet environment. However, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which interprets the ECHR with binding effect for Contracting States, has in nearly 300 instances applied rights from the Convention in environmental cases. The ECtHR has not yet decided on appeals concerning greenhouse gas emissions. Whether the ECHR establishes a positive commitment to preventing dangerous climate change must be answered based on ECtHR methods in light of existing practice and the purpose of the Convention.

The right to life. Article 2 of the ECHR protects the right to life and obliges the State to protect against real and imminent danger to loss of life through environmental hazards. According to ECtHR practice, this protection includes general community risk. There is no doubt that the risk of dangerous climate change is real, but it is disputed whether the risk is immediate. In other types of cases, the ECtHR has considered hypothetical risks up to 20-50 years into the future within the scope of protection. Greenhouse gas emissions immediately change the balance of the atmosphere, with long-term effects from CO2 in particular. The risk of dangerous climate change is thus immediate and latent. In NIM’s assessment, this indicates that Article 2 of the ECHR applies. The report argues, based on ECtHR practice and international law, that the fact that several States are responsible for climate change does not provide exemption from liability.

The right to a home and privacy. Article 8 of the ECHR commits the State to protect the health and well-being of individuals in cases where a “sufficiently close link” has been established between a future environmental hazard and privacy interests or homes. The ECtHR has applied the provision to environmental hazards where the risk is contingent on several hypothetical causal chains, see e.g. Hardy and Maile. The risk of climate change is, as mentioned above, immediate and latent. It has been well established by UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports and national reports that greenhouse gas emissions cause climate change. The link is therefore “sufficiently close”, in NIM’s view. The provision is therefore generally applicable.

Adequate and necessary measures. The report argues that the Government will not have fulfilled its positive duty to safeguard the rights enshrined in Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR if decision-making processes prior to point source emissions do not comply with ECtHR requirements. In NIM’s view, neither will the Government have fulfilled its duty to safeguard if adequate and necessary measures have not been taken to avert the risk. What are sufficient measures can, by ECtHR methods, be determined based on other international law rules and consensus. There is a well-established international consensus that warming must be limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius to avoid harmful climate change. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), this will entail cuts of at least 25 percent by the end of 2020, and at least 45 percent by 2030, with net zero emissions by 2050. On the basis of this, the Dutch Supreme Court has concluded that emissions reductions of at least 25 per cent by the end of 2020 are necessary to avoid violating Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR.

Burden and margin of appreciation. An impossible or disproportionate burden cannot be imposed on individual States, and the ECtHR allows States a margin of appreciation (discretion) when considering measures. It is not clear whether States can expect a similar margin of appreciation in climate issues as the ECtHR has allowed in cases of environmental hazards that are “beyond human control”.

Can environmental associations appeal ECHR violations? Nationally, environmental protection associations have the right to invoke the ECHR by proxy, see Sections 1-3 and 1-4 of the Disputes Act . However, the right to appeal to the ECtHR is reserved for appellants who claim to be directly or indirectly affected by the violation. Where necessary to ensure the effective enjoyment of rights, the ECtHR has nevertheless accepted appeals from organisations over abstract violations without individualised victims, such as mass storage of data and secret surveillance. The report argues that it can therefore not be ruled out that the ECtHR could allow environmental organisations to appeal on personal rights violations that protect against harmful climate change.

Do UN human rights conventions grant rights concerning climate change?

Greatest threat. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights considers climate change the greatest threat to human rights. The UN Human Rights Committee, which monitors compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), has stated that climate change is one of the most urgent threats to the right to life and well-being of living and future generations. In environmental appeals, the Committee has stated that States must implement “all appropriate measures” to address the dangers of “general conditions in society,” including threats from pollution. The Committee has stated that the right to life can provide a protection against the real risk of life-threatening climate change, see Teitiota.

Climate appeals to UN agencies. UN human rights committees have received several individual appeals concerning climate change. One of the appeals has been made by Greta Thunberg and other children to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, alleging that the countries cited have violated the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child by not implementing emissions cuts in line with the 1.5-degree target to protect children’s right to life, health, culture and the best interests of the child. The appeal has not been settled.

Recommended halt to oil exploration. UN human rights committees have increasingly referred to greenhouse gas emissions in their recommendations to Norway. The UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment has argued that Norway has a human rights obligation to end oil exploration.

Are climate-displaced people entitled to international protection?

Climate-displaced people do not meet the conditions for being considered refugees under the Refugee Convention. However, in an appeal against New Zealand, the UN Human Rights Committee has stated that climate displaced persons could be entitled to international protection under Article 6 of the ICCPR, which guards against return in the event of a real risk of loss of life.

The ECtHR has not yet decided whether climate displaced persons are protected under Article 3 of the ECHR. The provision guards against deportation in the event of real risk of inhumane or degrading treatment in the country of origin. The ECtHR has previously stated that the protection applies regardless of the type of risk in question, and can be applied in a situation of extreme need “incompatible with human dignity”, see S.S. This may provide the basis for climate displaced persons in precarious situations being entitled to protection, but the issue must be considered unresolved.

What is the status of international climate actions based on human rights?

More than 1500 climate-related actions are in progress around the world, and at least 41 of them are based on human rights. The number is increasing. As of today, there are 11 ongoing and settled actions based on the ECHR, three appeals based on UN human rights conventions, one based on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, and several based on national human rights provisions. The rights most often invoked are the right to life, privacy, home, health, and property, as well as the right to an environment.

Lawsuits based on the ECHR have succeeded in the Netherlands, but have been rejected on procedural grounds in Switzerland and Ireland. The Irish action nevertheless succeeded based on national rules. The Swiss case has been appealed to the ECtHR. Lawsuits based on ECHR against planning decisions which would not in and of themselves result in GHG emissions have also failed in Norway and the UK. A common feature of several of the actions is disagreement over standing to try the cases before the courts, but agreement on the link between greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

How will NIM work on human rights-related climate commitments going forward?

NIM will monitor this area of human rights closely going forward. While this report has assessed obligations placed on governmental authorities, NIM will in the future also monitor companies’ compliance with the duty of care in the field of climate change, see the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP).

1. Introduction

The climate crisis is the greatest challenge of our time. It is the greatest threat to the realisation of human rights ever.1This report has been prepared by the Norwegian National Human Rights Institution (NIM). Chapter 2 of the report is written by CICERO Center for International Climate Research on commission from NIM. Technical adviser and lead author of the report is NIM Senior Adviser, Jenny Sandvig. Co-authors are Erlend Andreas Methi, NIM Senior Adviser, Mina Haugen, NIM Adviser, Marius Mikkel Kjølstad, research fellow at the University of Bergen (UiB) and NIM Associate Adviser, Agnes Harriet Lindberg, research fellow at the University of Cambridge and NIM Associate Adviser, as well as interns Matias Von der Lippe Sjursæther and Marit Tjelmeland, both master students at UiB. Thanks to NIM Director Adele Matheson Mestad, Assistant Director Gro Nystuen, and NIM Special Adviser Anine Kierulf, Associate Professor at the University of Oslo, for assistance and input along the way. Big thanks to NIM’s Communications Adviser Nora Vinsand for putting together images and content.

1.1. The background and purpose of this report

In January 2020, the then President of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), Linos-Alexandre Sicilianos, stated the following in a speech:

“We have unfortunately entered the Anthropocene age in which nature is being destroyed by man. In that context, more than ever, it is right and proper for the Court to continue with the line of authority enabling it to enshrine the right to live in a healthy environment. However, the environmental emergency is such that the Court cannot act alone. We cannot monopolise this fight for the survival of the planet. We must all share responsibility.”2Speech given on 31 January 2020 at the annual opening of the Court. See also the president’s speech at the high-level conference “Environmental protection and Human Rights”, February 28 2020 (in French). Both are available on www.echr.coe.int.

In October 2020, the new President of the ECtHR, Roberto Spano, stated in a speech on climate that:

“we are facing a dire emergency that requires concerted action by all of humanity. For its part, the European Court of Human Rights will play its role within the boundaries of its competences as a court of law forever mindful that Convention guarantees must be effective and real, not illusory.”

The ECtHR has not, to date, decided any cases on climate change. As of April 2021, the Court has communicated two climate cases from applicants in Portugal and Switzerland. In Norway, the Supreme Court in December 2020 ruled in favor of the Government in a climate action against exploration licenses in the Arctic. In December 2019, the Supreme Court of the Netherlands ruled in the Urgenda case that the country’s government had a human rights obligation to increase their targets for greenhouse gas emissions reductions, and similar climate actions based on the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and other human rights have been brought in several other countries. In recent years, the UN Human Rights Committee has made decisions on individual appeals and general comments concerning environmental damage and climate change.3See Chapter 6 of the report on climate in the UN human rights system and Chapter 8 on climate displaced persons, as well as Chapter 9 on human rights-based climate actions. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights considers climate change to be the greatest threat to human rights, ever.4See the opening remarks made by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, at the 42nd session of the UN Human Rights Council on 9 September 2019, available on www.ohchr.org, and the speech by the Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights, DunjaMijatović, at a high-level conference on environmental protection and human rights on 27 February 2020, available on www.coe.int. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights has also expressed concern that climate change and environmental decline threaten human rights.

Against the backdrop of these and other similar developments, NIM has in the past year chosen to highlight climate change and human rights. Our work has been based on a recognition of the fact that this is a field of great societal importance, where deeper insight is required.5The need for more research on climate and human rights in Norway in light of an expected legal development has been pointed out by Askeland, Cyndecka, Holmøyvik, Konow, Nordtveit and Schütz, “Klimarettslege utfordringar for rettsvitskapen” in Giertsen, Husabø, Iversen and Konow (eds.), Rett i vest. Festskrift til 50-årsjubileet for juristutdanningen ved Universitetet i Bergen (2019) pp. 177–196. The link between climate and human rights also raises several issues that have yet to be clarified, and of which this report can contribute to a better understanding.6See in particular Chapter 4 of the report on Article 112 of the Constitution and Chapter 5 on the European Convention on Human Rights.

The purpose of the report is twofold. Firstly, we want to contribute knowledge ourselves – about current law and recent developments in the field. Secondly, we hope that the report may stimulate further debate.

1.2. Some delimitations

NIM’s main purpose is to promote and protect human rights pursuant to the Constitution, the Human Rights Act and other legislation, international treaties and international law in general.7Act relating to the Norwegian National Human Rights Institution Section 1, second paragraph. See Section 3 for the Institution’s functions. That is to say that the basis for our work is the nature of human rights obligations. As far as this report is concerned, this means that it is beyond NIM’s mandate to have an opinion on the Government’s general climate policy. At the same time, human rights can create legitimate boundaries or restrictions on the political scope of action, in the field of climate change as much as in other fields. In accordance with our mandate, we will discuss these boundaries in the report. Such boundaries, however, are rarely unambiguous. This is especially true in an area of law such as this, where factual and legal developments occur rapidly. It is also important to emphasise that a human rights approach to the climate crisis is only one among several perspectives. Human rights alone cannot provide an answer to the climate crisis.

In general, the report will not deal with other aspects of the environment than those concerning global warming. Some of the discussions, for instance on the ECHR, will nevertheless build on case law concerning more local pollution and other forms of environmental damage that may by comparison be relevant to climate issues. In addition, some of the questions raised, such as the interpretation of Article 112 of the Constitution, may also have relevance to other types of environmental issues.

Human rights are based on the fundamental principle that States have a responsibility to respect and safeguard human rights only within their own jurisdictions.8See e.g. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Art. 1. The concept of jurisdiction, however, has been interpreted to encompass situations of effective control over territory or persons outside the State’s territory. The question of jurisdiction and climate change can raise difficult and legally unresolved issues. The Supreme Court recently held that Section 112 of the Constitution encompass exported emissions from Norwegian oil and gas, since the combustion cause harm on Norwegian territory. These types of issues will be dealt with in the report. Issues such as burden-sharing and international solidarity, however, will not be addressed.

1.3. The report’s structure

In the following chapters, we will first address two basic prerequisites for the substantive legal discussions in the remainder of the report. The first is the scientific evidence base for climate change. In Chapter 2, From emissions to climate risk, CICERO – the Center for International Climate Research, on commission from NIM, describes the current evidence basis for climate science. The second prerequisite is the conceptual Link between climate change and human rights, which will be addressed in Chapter 3. In addition to addressing some general challenges with viewing climate from a human right perspective, the chapter provides a more in-depth justification for the topics highlighted in this report.

Subsequent chapters address the various human rights affected by climate change. Chapter 4 addresses Article 112 of the Constitution, Chapter 5 the European Convention on Human Rights, and Chapter 6 the UN human rights system. In addition to these substantive provisions, Chapter 7 will address procedural rights covered by these three legal bases.

In Chapter 8, we look at the development of human rights obligations to provide international protection to climate displaced persons. In chapter 9, we keep our eyes on international developments when presenting central human rights-based legal cases. The cases we refer to relate mainly to the interpretation of international conventions that Norway is bound by, and these cases can therefore indirectly contribute to how the Norwegian obligations may be understood. In the final chapter, we consider the way forward.

2. From Emissions to Climate risk – Scientific Knowledge Base

This chapter is written by CICERO – the Center for International Climate Research1The chapter is written by CICERO Center for International Climate Research (hereinafter CICERO), and is dated 26 August 2020. Authors are Bjørn H. Samset and Marianne T. Lund. on commission from the Norwegian National Human Rights Institution (NIM).2A basic premise for discussions about the relationship between climate and human rights is an understanding of the scientific link between greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. Since NIM’s expertise is human rights, we have commissioned CICERO to summarise and explain the scientific knowledge base in Chapter 2 of the report. CICERO’s descriptions form the factual basis for our legal discussions in the rest of the report.

2.1. Introduction

The chapter summarises the scientific basis for linking greenhouse gas emissions and other man-made influences on the global climate to an increased risk of adverse and harmful effects on nature and society. The main source for the chapter is the Fifth Assessment Report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC),3 Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, Cambridge University Press (IPCC AR5 (2013)). as well as updates from three recent special reports.4 Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate. World Meteorological Organization, Genève, Switzerland (IPCC SR15 (2018)); Climate Change and Land. An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland (IPCC SRCCL (2019)) and Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. An IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland (IPCC SROCC (2019)). Some recent scientific literature has also been used, with references in footnotes.

The chapter’s main conclusion can be summarised as follows:

Any human activity that changes the climate, locally or globally, from the State to which society and nature are currently adapted, can lead to an increase in climate-related risk. Natural variations, which are a part of the climate to which we are accustomed, make society relatively resilient against minor changes. In most places, however, human activity has already significantly changed the temperature relative to these variations.5Hawkins, et al., “Observed Emergence of the Climate Change Signal: From the Familiar to the Unknown,” Geophysical Research Letters vol. 47 (6) (2020). Continued climate impact, especially from CO2 accumulating in the atmosphere and thereby causing further warming in both the short and long term, therefore immediately contributes to exacerbating many types of climate risks. Climate risk is generally considered to increase in step with global warming and is, for instance, significantly greater at 2 degrees than at 1.5 degrees.6SR15 (2018). Climate change is already contributing to an increase in many types of climate risks, for both nature, society and people. Further emissions, including from Norway, will intensify this risk, both locally and globally.

In the following, we elaborate on and substantiate these conclusions.

2.2. Climate change, natural variability and climate risk

Climate change is now observed throughout the climate system, from deep down in the oceans to high up in the atmosphere. Today, around the year 2020, the global surface temperature is about one degree higher than in pre-industrial times.70.87 degrees for the decade 2006–2015, relative to 1850–1900, followed by four years all measured to be warmer than this average. See IPCC SR15 (2018) and WMO (2020). The trend over the past 50 years has been a global warming of just under 0.2 degrees per decade. This increase in temperature, and the recorded increase in the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere over the same period, has occurred very rapidly from a geological time perspective. The current level of CO2 in the atmosphere is also higher than it has been in a million years.8See illustration of development over time at the end of the chapter. Significant changes have also been measured across the climate system, including in the oceans (warming, sea level rises, acidification), on land (heat waves, extreme rainfall, tropical hurricanes) and in the frozen parts of the Earth (melting glaciers, ice loss in Greenland and Antarctica, Arctic sea ice decline, reduced snow cover during winter in the Northern Hemisphere).

Global warming, and the other climate changes, are mainly attributable to man-made influence, with only a small contribution from natural causes such as variations in solar radiation, volcanoes and cyclic changes in ocean currents. Of the man-made impacts, greenhouse gas emissions are by far the most forceful,9CO2, methane, nitrous oxide, ozone and synthetic gases; a total of around 1.5 degrees in recent model studies (Tokarska et al.,”Past warming trend constrains future warming in CMIP6 models,” Science Advances vol. 6 (12) (2020)). while emissions of aerosols (particles suspended in the air, such as soot, dust and sulphur compounds) in sum have a cooling effect, thereby so far keeping global warming somewhat at bay (cooling at around 0.5 degrees).10Tokarska et al. (2020); Samset et al, “Climate Impacts From a Removal of Anthropogenic Aerosol Emissions”, Geophysical Research Letters vol. 45 (2) (2018) pp. 1020-1029.

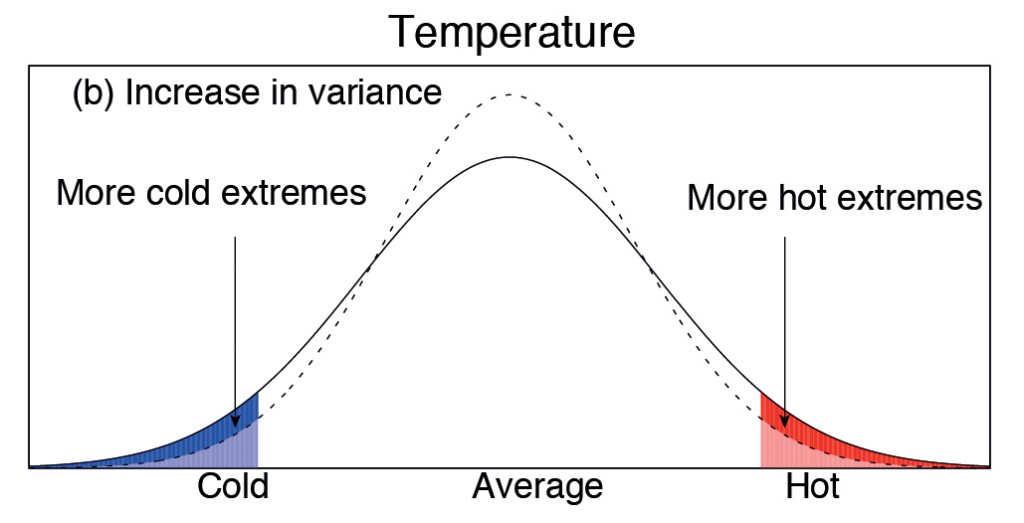

(IPCC AR5)The degree of natural variability, or how much temperature, precipitation and other parts of the weather normally vary from day to day, season to season and year to year, is as important a part of the climate as the average values. Nature and society are normally adapted to both. The amount of variability, however, is very different in different parts of the world, and is generally higher at high latitudes (as in Norway) than closer to the equator.11Hawkins, et al. (2020). At the same time, climate change occurs at different rates in different places. Warming also occurs faster in the north than near the equator, and faster on land than over oceans. For instance, an observed warming of between 3 and 5 °C has been reported from 1971 to 2017 at measuring stations in Svalbard.12Hanssen-Bauer, et al. (eds.), Climate in Svalbard 2100 – a, knowledge base for climate adaption, NCCS report no. 1 2019. Available on https://www.miljodirektoratet.no/globalassets/publikasjoner/M1242/M1242.pdf Climate change affects averages, but can also change variability. See Figure 1, which shows an example of how a warming and a simultaneous change in variability can lead to an increase in very hot days, while there are still as many cold days as before.

Society’s climate risk is mainly determined by three factors: the physical climate change (such as stronger heatwaves or more intense extreme rains), how exposed we are to the change (whether it happens in areas with high population density, or far out at sea), and how vulnerable we are to it (whether agriculture and infrastructure have already adapted to the changing climate, or whether conditions go beyond the limits of tolerance). Because natural variations will always occur on top of the average properties of the climate, even relatively small human-induced changes to the mean can lead to weather and climate events that are beyond those which society is familiar with and adapted to.13Hawkins, et al. (2020).

2.3. From emissions to climate change, in the short and long term

Recent research on the effect of climate change on nature and society shows that while a higher temperature is not the direct cause of all types of climate-related risks, the degree of global warming is nevertheless a good measure of the degree of climate risk. A central question is therefore how man-made emissions contribute to surface warming, in the short and long term. The physical processes linking emissions to warming are scientifically well established, and the remaining uncertainties about how strongly the climate responds to different types of emissions are limited.

Some types of emissions, such as soot, sulphur compounds and other forms of air pollution, have a direct impact on solar irradiance. The particles can reflect the solar radiation back into space (by themselves or by making clouds whiter), or absorb solar radiation before it reaches the Earth’s surface. The ground thereby cools quickly. Most of these emissions, however, remain in the atmosphere for only a few days. If, for instance, we removed all air pollution, the response of the climate would therefore in principle manifest within a few weeks to months. However, see the comments on the natural variability and inertia of the climate system further down.

An increase in the amount of greenhouse gases, as a result e.g. of the burning of oil, coal and gas, also has a rapid effect. A stronger greenhouse effect enhances the absorption of thermal radiation (heat) from the Earth’s surface, similar to the way a down jacket retains heat from the body. Like with a down jacket, however, it takes a little time for the full effect to be felt. If we abruptly doubled the amount of CO2, for instance, we could in the long term expect around 3 °C global of warming, according to the latest research.14Sherwood, et al., “An assessment of Earth’s climate sensitivity using multiple lines of evidence,” Reviews of Geophysics (2020). Around half of this warming would have occurred during the first decade, much of the remaining warming over the next hundred years, and then a small remnant on a millennial scale.15Ibid.

In reality, the greenhouse effect increases slightly each year as emissions continually increase (except in the pandemic year 2020), which in turn contributes to increased warming. The warming we register today, from year to year, is the sum of all these consecutive influences over time on climate, combined with natural variations from year to year of a few tenths of a degree.

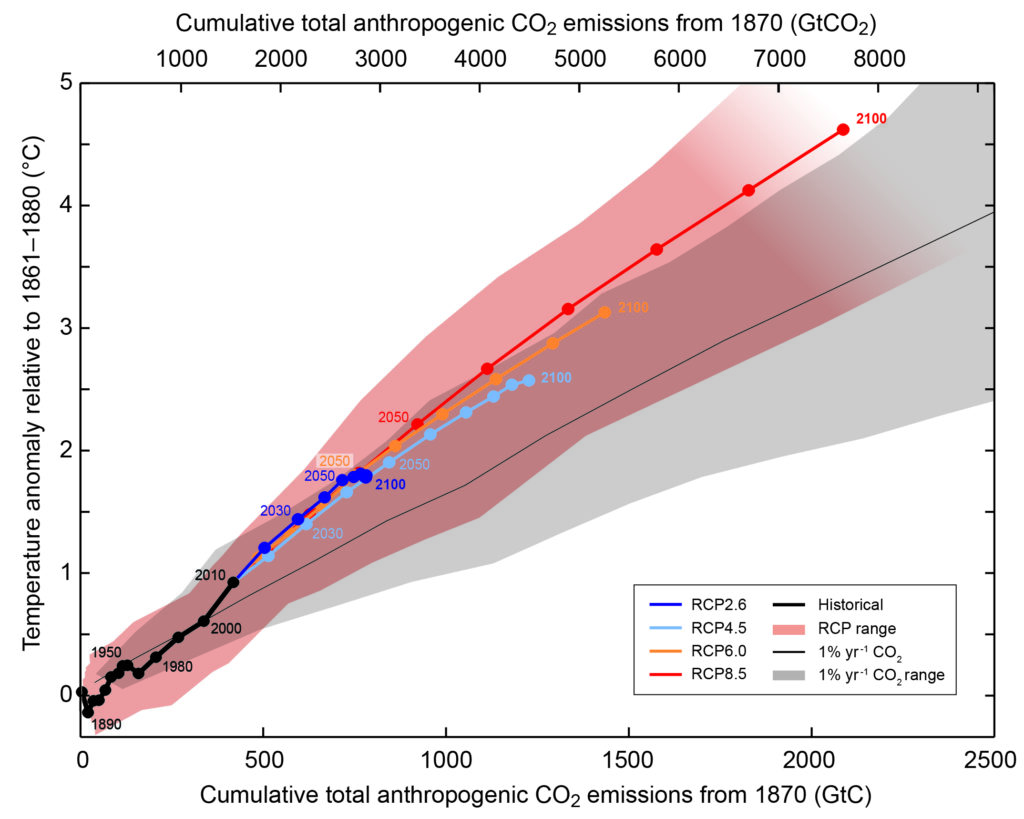

To simplify this complex picture, scientists have concluded that there is a relatively direct relationship between the sum of all CO2 emissions from pre-industrial times until we cease producing them and how strong the eventual global warming will be. See Figure 2. Based on this, it is possible to estimate the level of future warming, under a given assumption about future emissions of CO2 – and thus, as we will see, also how significant the climate risk will be. The key message, however, is this: All emissions affect the climate from the moment they are released into the atmosphere, but some – especially CO2– also have a long-term effect.

The long-term evolution of climate change depends on how emissions continue to progress, and whether we at some point in the future develop technology or actively manage the environment in such a way as to remove greenhouse gases from the atmosphere on a large scale. As of today, all the scenarios applied by the IPCC in SR15, and where we remain within the goals of the Paris Agreement, depend on such technology or management in the second half of this century. This will require significant upscaling, development, and improvements of technology. Not even the most climate-optimistic scenarios, where human-made greenhouse gas emissions and carbon uptake are in balance already in 2050 and emissions turn negative with the help of technology thereafter, show a notable reduction in the global temperature below 1.5 to 2.0 degrees before 2100. Higher emission scenarios show continued warming for several hundred years. The natural carbon cycle, along with any form of technological or otherwise elevated atmospheric carbon removal, will drive the temperature down again in the long term, but only in a situation where anthropogenic emissions are net zero or negative. Technological carbon removal to reduce temperatures must therefore come in addition to that used to offset residual anthropogenic emissions. Climate change can therefore be considered permanent and irreversible on all timescales relevant to social and political development.

2.4. From climate change to climate risk

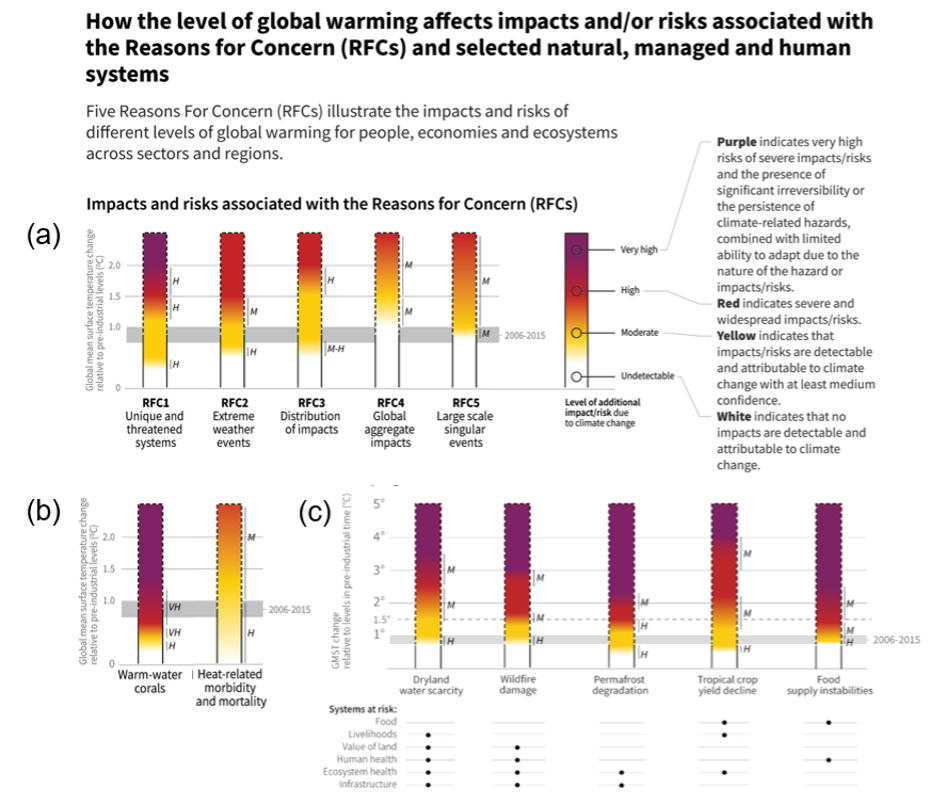

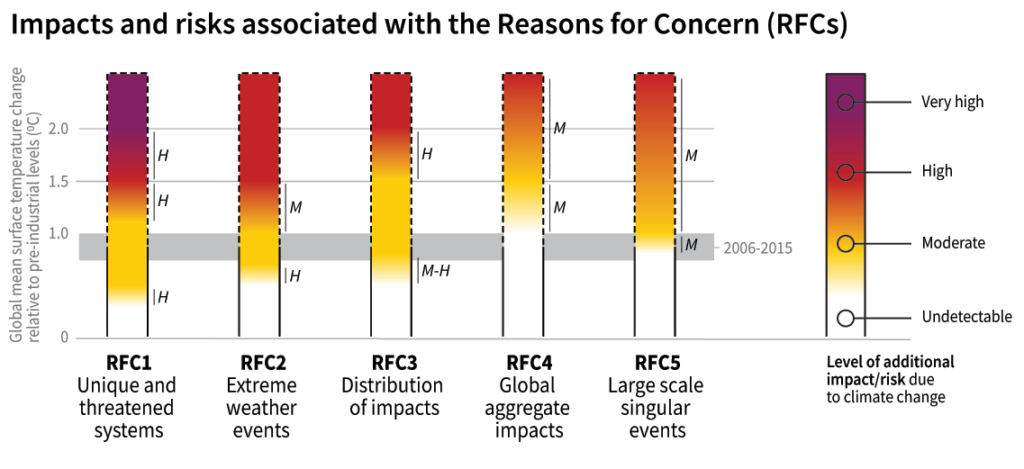

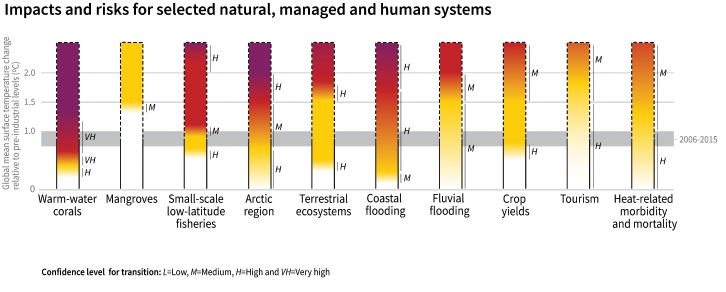

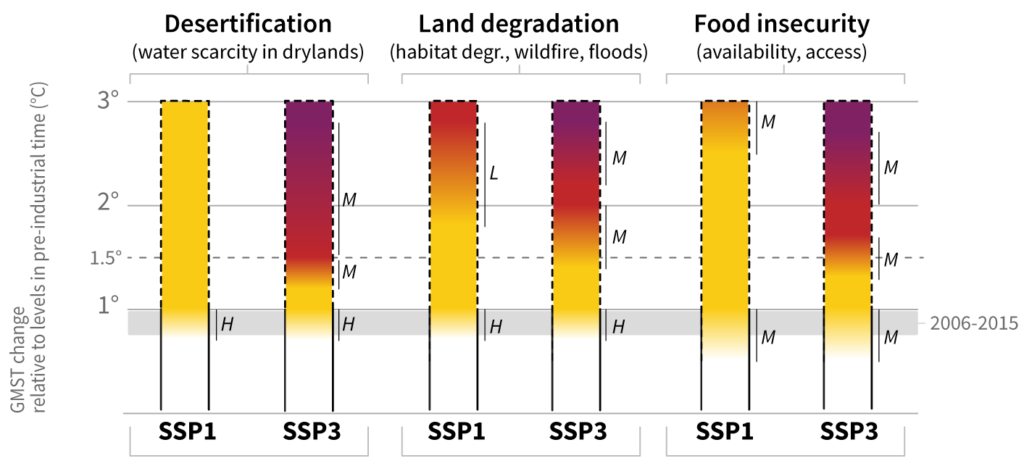

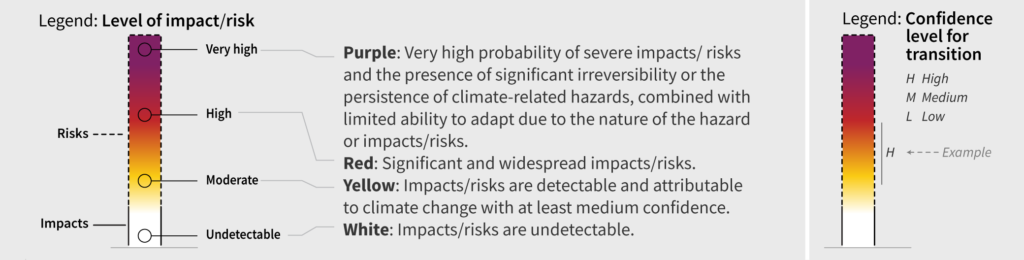

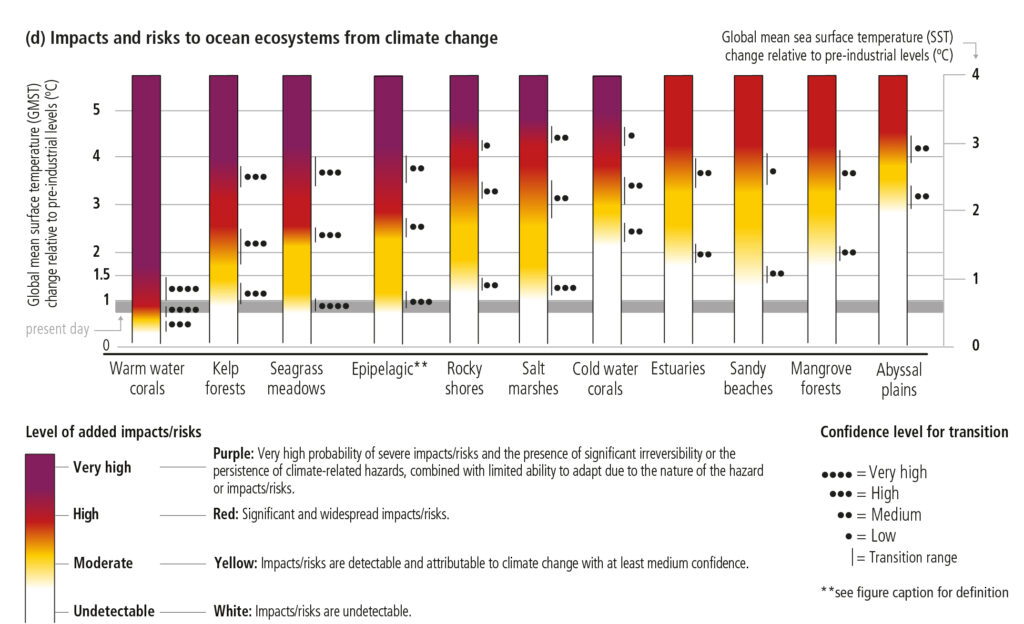

When current emissions have now been linked to continued climate change, the next step is to link climate change to climate risk. Today, this is often done through so-called “burning ember” charts; coloured columns where the level of global warming increases upwards, and the darker colour indicates higher risk. See an example in Figure 3, taken from two of the IPCC’s special reports from 2018 and 2019. At the end of the chapter we include the summary figures on risk from all three special reports. Together, they provide a thorough picture of how climate risk for different human and natural systems increases with the degree of warming.

Figure 3 has three parts. Part (a) and (b) are from the Special Report on 1.5-degree warming. Part (a) shows an overall risk assessment for aggregated changes, such as extreme weather and particularly harmful individual events. Part (b) shows more detailed assessments of the impact of climate change on coral reefs and on heat-related disease and death in humans. Part (c) is from the Special Report on Climate Change and Land, and shows risks related to water shortages in dry areas, large fires, loss of permafrost, failed harvests in tropical areas and unstable food supply. Below part (c) is an indication of which foundations of society is most at risk: food, livelihood, health etc. Note that the columns here extend to greater warming than in parts (a) and (b). (See also the appendices for the full figures.)

There are two overarching messages in these figures. The first is that the risk steadily increases with global warming, sometimes faster, other times somewhat slower. The second is that for the current level of warming (calculated for the period 2006–2015), indicated by the grey horizontal band, moderate climate risk has already been established in most cases. We are therefore already in a situation where climate change poses challenges for nature, society, health and life, in the form e.g. of fires and heatwaves. Any further warming, from further emission of greenhouse gases or other causes, will heighten this risk. In many cases, two degrees of global warming could be enough to move us into the high-risk area, defined as “severe and widespread impacts/risks”, where risks include irreversible consequences such as tipping points in the climate system (e.g. self-reinforcing emissions of methane from tundra in the north, or changes to global ocean currents).

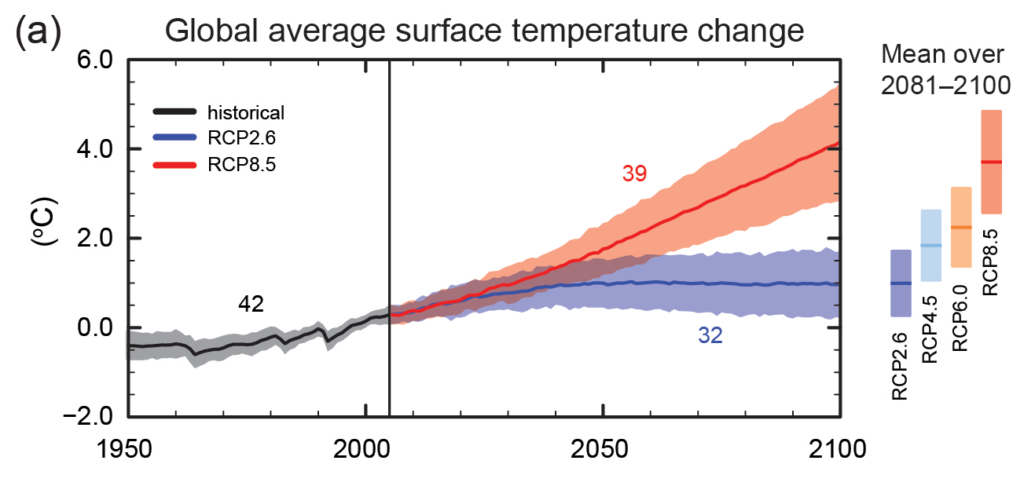

2.5. Society’s impact on risk

As mentioned above, climate risk is determined by three factors: physical climate changes, exposure and vulnerability. The physical changes are largely determined by how warm it gets, and consequently by how much greenhouse gases we emit in the future. Figure 4 shows the span of temperature development up until 2100 in the scenarios used in IPCC AR5. Here, RCP8.5 is an assumption of continued high, and increasing, greenhouse gas emissions (with an associated CO2 concentration in 2100 of around 1200 ppm), while RCP2.6 (CO2 concentration in 2100 of 400 ppm) assumes reductions that overall are in line with the ambitions of the Paris Agreement. The figures are relative to the average of temperatures in 1986–2005, where global warming was already at 0.61 °C. In order to arrive at total warming from pre-industrial times, this number must therefore be added. The figure shows that we can expect warming between 2.0 and 4.5 °C by 2100, as the two scenarios shown can be roughly considered the upper and lower range of what might happen to emissions. By comparison, scientists estimate that the future emission cuts announced by the world’s nations before the Paris Agreement would have resulted in a warming of around 3°C by 2100 (relative to 1850–1900), if successfully implemented but not further strengthened.16NB: These scenarios look only at man-made emissions and the expected behaviour of the carbon cycle, and do not include any abrupt feedback/tipping points. These, however, are included in the other parts of the risk assessments below.

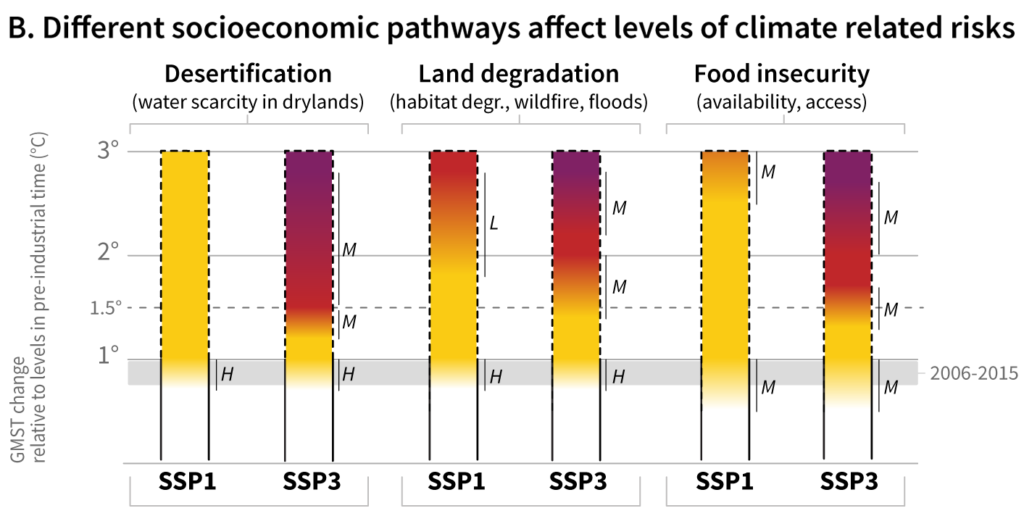

The risk, especially exposure and vulnerability, is nevertheless also affected by societal factors. In later reports, the IPCC has used scenarios that describe possible future socioeconomic developments, in addition to emissions and climate change. Studies of these show that even for the same degree of warming, and thereby comparable physical changes, the climate risk will be significantly lower in a society characterised by international cooperation and sustainability than in a world with a high degree of conflict and resource use. At the same time, socioeconomic development alone is not sufficient to avoid elevated climate risk. See Figure 5, which also describes the two illustrative scenarios for socioeconomic development (called SSP1 and SSP3).

2.6. Norwegian emissions and Norwegian risk

Climate change is a global issue. Emissions of greenhouse gases such as CO2 and methane disperse throughout the entire atmosphere, regardless of their origin, causing changes both locally and globally. Climate risk in any given place, such as Norway, therefore depends on the degree of global warming, on which physical changes are most prominent regionally and locally, and on how exposed and vulnerable society is where they occur. For Norway, extreme rain, floods, landslides, wildfires, migration of new species and diseases and agricultural challenges have been mentioned, but this list is not exhaustive. Furthermore, Norway is also vulnerable to risks associated with major changes abroad, affecting trade, security and international relations. Quantifying Norway’s climate risk in detail is an ongoing activity among scientists, authorities and corporations.17Se e.g. https://klimaservicesenter.no/faces/desktop/index.xhtml.

In 2019, 42 million tonnes of CO2 were emitted from Norwegian territory (total greenhouse gas emissions of 50 million tonnes of CO2 equivalents).18SSB 2020, https://www.ssb.no/klimagassn/. This represents approximately 0.12% of the total man-made CO2emissions of 36 trillion tonnes of CO2 that same year.19Global Carbon Project 2019, www.globalcarbonproject.org/carbonbudget. In comparison, the burning of oil and gas extracted from Norwegian territory and sold abroad causes approximately20Figures for 2019, based on estimates from the Global Carbon Project (see previous note). ten times as much emissions, which is more than 1% of the global total. Emissions directly from Norwegian territory, and from use of the oil and gas Norway produces, both contribute to increasing climate risk – globally and locally.

2.7. Additional figures

Risk chart from IPCC’s three special reports from 2018 and 2019:

How the level of global warming affects impacts and/or risks associated with the Reasons for Concern (RFCs) and selected natural, managed and human systems21Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C (IPCC SR15).

Five Reasons For Concern (RFCs) illustrate the impacts and risks of different levels of global warming for people, economies and ecosystems across sectors and regions.

Red indicates severe and widespread impacts/risks.

Yellow indicates that impacts/risks are detectable and attributable to climate change with at least medium confidence.

White indicates that no impacts are detectable and attributable to climate change.

A. Risks to humans and ecosystems from changes in land-based processes as a result of climate change22Special report on Climate Change and Land(IPCC SRCCL)

Increases in global mean surface temperature (GMST), relative to pre-industrial levels, affect processes involved in desertification (water scarcity), land degradation (soil erosion, vegetation loss, wildfire, permafrost thaw) and food security (crop yield and food supply instabilities). Changes in these processes drive risks to food systems, livelihoods, infrastructure, the value of land, and human and ecosystem health. Changes in one process (e.g. wildfire or water scarcity) may result in compound risks. Risks are locationspecific and differ by region.

B. Different socioeconomic pathways affect levels of climate related risks23Special Report on Climate Change and Land(IPCC SRCCL)

(d) Impact and risks to ocean ecosystems from climate change24Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (IPCC SROCC)

3. The Link Between Climate Change and Human Rights

Climate change has enormous consequences for nature and the environment. This chapter conceptualises the link between climate and human rights.

3.1. Introduction

There is a clear link between climate risk and the interests that are protected by human rights.1Bugge, Lærebok i miljøforvaltningsrett (5th ed., 2019) p. 113. A damaged climate system will affect nature as we know it, and lead to more droughts, extreme rainfall, storms, sea level rises, heatwaves, wildfires, landslides and floods. This will again have consequences for fundamental human interests.2See Chapter 2 of the report, written by CICERO on commission from NIM. Both people and buildings will fall victim to landslides and floods, the food supply will be threatened, groundwater may become undrinkable as a result of salination, and new diseases will spread.3See Chapter 6 of the report on climate in the UN human rights system. In both the short and long term, a damaged climate system could lead to rising tensions globally. Climate change could also lead to many people being displaced from their homes.4This issue is discussed in more detail in Chapter 8 of the report on climate displaced persons.

At the same time, many would consider it misguided to justify environmental protection with an “anthropocentric” or human perspective, rather than attributing an intrinsic value to nature.5See more detailed criticism of the ecophilosophical criticism of human rights in Bugge (2019) p. 114. We will not enter into this debate here, but point out that human rights can include environmental interests, as illustrated in the jurisprudence of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR). Firstly, human rights can provide protection extending beyond individuals. Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR, for instance, can provide protection against generalised risks in environmental matters, and Article 112 of the Constitution protects the intrinsic value of nature. Secondly, human beings themselves are part of nature. In the climate field, this is particularly evident. One cannot therefore meaningfully protect human life and health without consideration of climatic conditions for life and health.

Another objection is that climate change is a political issue with such complex causes and effects that it is not suitable for human rights doctrines. Before entering into this discussion (Section 3.3), we will outline how the connection between climate change and human rights manifests in three relations; prevention of climate change (3.2.1), adaptation to climate change (3.2.2) and as boundaries to climate action (3.2.3). The overview will explain why this report leaves certain human rights issues aside for now, and concentrates on issues that appear unresolved.6See the report’s introduction.

3.2. Three human rights aspects

Within international climate cooperation, it is common practice to refer to two different types of actions required to deal with climate change, namely adaptation and mitigation. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has established various working groups to contribute to its reports, with Working Group II looking at how we need to adapt to climate change to avoid harm, and Working Group III looking at what emissions reductions are required for the climate system to stabilise before the average warming reaches 2 degrees Celsius. Both of these types of actions are covered by the Paris Agreement, where Article 4 deals with reducing greenhouse gas emissions, while Article 7 deals with adaptation to inevitable changes. This distinction is also often referred to in the context of Norwegian climate change policies, e.g. in NOU 2018: 17 Klimarisiko og norsk økonomi.7NOU 2018: 17 Klimarisiko og norsk økonomi, p. 14. In the following we will show how these two situations also have a human rights aspect. In addition, we will highlight how human rights have been emphasised as an important barrier in the choice of means to achieve adaptation and mitigation.

3.2.1. Mitigation of climate change

The relationship between human rights and climate that is most fundamental and, at the same time, the least explored is the responsibility for limiting climate change. This relationship concerns whether the government has a human right obligation to fight climate change, i.e. to refrain from new large greenhouse gas emissions and reduce current emissions.

The question of whether States have human rights obligations to avoid climate change is not new, and today a comprehensive international legal framework exists in this area.8The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was negotiated at the Rio Conference in 1992. This Convention has subsequently been operationalised through the Kyoto Protocol, which regulated emissions from 2008 to 2012. In the Doha Agreement, Norway committed to extend the Kyoto commitment for a second term until 2020. Today, the most important international climate agreement is the Paris Agreement, which was negotiated in 2015. Norway’s participation in international climate cooperation is incorporated into Norwegian law through the Climate Change Act of 2017. Here, Norway has committed to becoming a low-emission society in 2050 in line with the Paris Agreement. This law is based on the two agreements on climate policy from the Norwegian Parliament in 2008 and 2012. The fact that there is a link between human rights and climate is directly evident from climate cooperation. The Paris Agreement’s preamble, paragraph 11, contains a concrete recommendation that States should “consider” their obligations under “human rights” and “intergenerational equity” when taking action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Article 1 defines “adverse effects of climate change” as changes that will have “significant deleterious effects” on inter alia “human health and welfare”.

In the 1972 Stockholm Declaration, the first part of the first principle adopted said the following:

“Man has the fundamental right to freedom, equality and adequate conditions of life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being, and he bears a solemn responsibility to protect and improve the environment for present and future generations.”9Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, 1972.

A few months earlier, the first proposal for an environmental provision in the Norwegian Constitution had been put forward – the proposal did not get a majority, but started a process leading up to the adoption of what became Article 110b (currently Article 112) of the Constitution.10Regarding the proposal from January 1972, put forward by Helge Seip, member of the Norwegian Parliament, see Bugge, “Grunnlovsbestemmelsen om miljøvern: Hvordan ble den til?” in Fauchald and Smith (eds.) Mellom jus og politikk. Article 112 of the Constitution (2019) pp. 19–40, at pp. 20–21. In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development released its report “Our Common Future,” which, among other things, proposed a set of legal principles for environmental protection and sustainable development. The first legal principle proposed was that “[a]ll human beings have the fundamental right to an environment adequate for their health and well being.”11Report of the World Commission on the Environment and Development, Our Common Future (1987). In the 1990s, Article 110b of the Constitution was adopted in Norway (1992) and the Aarhus Convention in Europe (1998), and in addition, the issue of climate and human rights was discussed by legal scholars.12Fauchald, “Miljø og menneskerettigheter”, Kritisk juss 1989 p. 3–17; Fauchald, “Bør retten til miljø anerkjennes som menneskerettighet?”, Retfærd 1991 no. 53, p. 68–70; Bugge, “’Bærekraftig utvikling’ og andre aktuelle perspektiver i miljøretten”, Lov og Rett 1993 no. 8, pp. 485–498, Section 4.1.

Ever since 2008, the UN human rights agencies have dealt with the link between human rights and climate change.13See Chapter 6 of the report on climate in the UN human rights system. In 2016, the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment pointed out that human rights also relate to the issue of “how much climate protection to pursue.”14A/HRC/31/52, paragraph 33. In recent years, the issue of climate change and human rights has increasingly been raised in legal cases before national and international fora.15See chapter 9 of the report on climate-relate legal cases based on human rights. These cases have necessitated a clarification of what the legal obligations in this area entail. In Chapters 4, 5, 6 and 7, NIM will discuss the commitments to avert climate change that result from the Constitution and the international conventions on human rights that Norway has ratified.

3.2.2. Adaptation to climate change

Another human rights aspect of climate change concerns the obligation to make local adaptation to the climate change that already has or will inevitably occur. This obligation is to a large extent already settled in case law. Given the circumstances, States have an obligation to protect citizens from specific and predictable threats from environmental and natural disasters.16A/HRC/31/52, paragraph 37. Although several natural disasters are inevitable, it is clear that much can be done to avert impact on people’s lives and rights.17See e.g. A/64/255, paragraph 51. Various UN agencies have addressed, among other things, the importance of disaster planning,18UN’s Human Rights Council, CCPR/C/GC/36, paragraph 26, and UN’s Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women, CCPR/C/GC/37, Gender-related dimensions of disaster risk reduction in the context of climate change. that food supply systems need to be reformed,19The UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food, see A/HRC/25/53. and that residential houses must be secured through risk analyses for urban planning and construction.20The UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing, see A/64/255, paragraph 51.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) has also on several occasions heard cases relating to States’ obligations in environmental disasters.21 Budayeva et al. v. Russia and Özel et al. v. Turkey. For more, see Chapter 5 of the report on the European Convention on Human Rights and climate. Similar obligations can likely be derived from the parallel provision of rights in Articles 93 and 102 of the Constitution, as well as Article 112. National adaptation is therefore an important human rights obligation in the face of climate change. However, we will only to a limited extent discuss adaptation obligations in this report. The focus rests on the more fundamental commitment to avert any harmful impact on the climate system in the first place.

We will nevertheless address one particular issue concerning adaptation to climate change that has occurred or will inevitably occur, and that is the legal status of climate displaced persons. When the natural environment changes so much that people are forced to leave dangerous areas, it raises the question of whether they have the right to settle in safer areas outside their own country. This is an ever-evolving field that we will discuss in more detail in Chapter 8.22See Chapter 8 of the report on climate displaced persons.

3.2.3. Boundaries to climate action

A third human rights aspect of climate change is the notion of human rights as boundaries or limitations on measures to address climate change. Human rights entail boundaries for political agency in that political goals cannot be implemented in a way that violates human rights. The duty of the government to respect property rights, indigenous rights, protection against discrimination, the protection of privacy, freedom of expression etc., does not cease to apply even if certain acts of government threatening these rights in isolation may have worthy purposes. According to the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, this applies also in principle to climate policy.23See e.g. A/HRC/31/52, paragraph 33 ff.

Whether the government’s policies and measures to address climate change are in conflict with other rights depends on how these actions are arranged. Whether rights have been violated will depend on a concrete assessment of the rights in question and the measures in question.24Wewerinke-Singh, State Responsibility, Climate Change and Human Rights under International Law (2019) pp. 125–127. In this report, NIM will not make an abstract assessment of how other rights may be affected by government climate action. We will, however, make two observations that show the tension in the relationship between climate and human rights. Firstly, it is important that the government is aware that climate action can also be in conflict with other rights, and that this is taken seriously in climate change action, as in any other form of exercise of authority. It is not thereby said that climate action cannot interfere with other protected rights. Generally, however, it is important that the authorities consider whether the measure is appropriate, necessary and proportionate before intervening. In connection with large-scale renewable energy projects in indigenous areas, it has been particularly necessary to raise awareness of human rights consequences.25See e.g. Khan, Working paper on promoting rights-based climate finance for people and the planet (A/HRC/WG.2/19/CRP.4) and Bugge (2019) p. 115.

At the same time, it is important to clarify that the protection of the climate is a human rights issue. The preparatory work for Article 112 of the Constitution, for instance, raised the questions whether “the right to a healthy environment is not at least as important to the existence and self-realisation of the individual as the other human rights”.26Document 16 (2011–2012) Report to the Presidency of the Norwegian Parliament from the Human Rights Committee on Human Rights in the Constitution, p. 245. Protecting the climate is therefore a legitimate purpose for the government and this must be given sufficient weight in the face of other considerations and rights. A practical example is that the government could have a duty to intervene in property rights or business interests in order to safeguard climate concerns. In the same way that the restrictions in the right of disposal in property law is not absolute, the proportionality assessment for other rights also addresses the reason why the government is taking action.27See e.g. Bugge (2019) p. 47 ff. When assessing whether interventions in other rights are necessary and proportionate, the purpose of safeguarding commitments to avert climate change will have to be given considerable weight.28See Chapter 4 of the report on Article 112 of the Constitution and Chapter 5 on the European Convention on Human Rights and climate.

3.3. Key issues when mitigation of climate change is understood from a human rights perspective

In this report, there are some issues that appear several times. The first is whether climate is exclusively a political issue and not a legal one. Another issue is whether we have human rights obligations to future generations, given that they will bear the long-term and irreversible consequences of climate change. We will discuss these two issues throughout the report. In the following, we will nevertheless introduce them on a general level, as a framework for further discussions.

3.3.1. Politics or law?

A central objection to applying human rights obligations to the prevention of climate change is that the subject is considered political. This understanding is based on three considerations. The first is that the government’s understanding of and response to climate change is politically contentious. Another objection is that there are various policy instruments that can be applied to prevent further climate change. The choice between instruments is a typical political assessment. This objection is closely linked to the last consideration, which is that combatting climate change is just one of many goals pursued by the government and society at large. It is up to politicians how this goal should be reconciled with other worthy purposes.

The fact that a field is politically contested and depends on priorities is, however, true for many areas where boundaries are set by human rights. One example is immigration policy, in which the prohibition on inhumane treatment and the right to private and family life can limit the State’s right to decide who should be allowed to remain within their territory. The fact that climate change is an area that is at the centre of political debate is in itself not sufficient for this form of exercise of authority to be dissociated from human rights obligations. The fact that greenhouse gas emissions, unlike other fields, could have irreversible consequences for future generations, which are not currently represented in the political system, may also imply that the interests of posterity must be safeguarded through legal limitations or boundaries on the agency of the present majority.

3.3.2. Future generations as rights-bearers

Because climate change is long-term, the impact of current emissions will affect generations who are not yet alive. This raises questions of a more legal philosophical nature about whether the people who will live in the future have human rights, and whether these possible human rights could commit us to climate action today. This is often referred to as a matter of justice across generations (“intergenerational justice/equity”).29Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Intergenerational Justice, available on https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/justice-intergenerational/ Within international climate cooperation, this future perspective has been clear from the very start. In the preamble to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, Art. 3 says that “the Parties should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind,” and future generations are mentioned specifically in the preamble. The Paris Agreement also states that nations should consider “intergenerational equity” in efforts to avert climate change. As a philosophical question, it typically raises three challenges, which we will discuss in turn. The first of these is often referred to as Parfit’s non-identity problem.

(i) The non-identity problem

The first philosophical challenge associated with future generations as rights holders was put forward by Derek Parfit in the 1980s and concerns our current actions affecting the identities of those who will live in the future.30Parfit, Reasons and Persons (1986) pp. 358–359. This is because the way in which we live today, such as where and what we study and work with, will affect who we meet and when we have children – and thereby also which children are actually born. It therefore appears to be a paradox if these future children were to blame us for our neglect of the climate problem, since the actions that led to the climate problem may be exactly the same actions that allow these individuals to exist. For Parfit, it therefore does not make sense to say that specific future individuals have rights relating to us taking actions that would have led to these individuals not existing.

However, the tension between the interests of specific individuals in having been born and their interests in being born into a stable climate, can be solved if we treat these future individuals as a group.31See e.g. Lindberg, “Fremtidige generasjoner som rettighetsbærere”, Salongen nettidsskrift for filosofi og idéhistorie, published March 30 2020. Accessible on salongen.no. At a group level, there is a difference between a potential group of individuals coming into the world in an environment with a stable climate, and a potential group of individuals coming into the world in an environment where the tipping points of climate catastrophe have been reached. From a collective standpoint, Parfit’s paradox disappears, allowing future generations to possess human rights.

However, as the consequences of climate change draw closer, many argue that the non-identity problem is irrelevant to our understanding of climate change. Children born today will be 80 years old when we reach 2100, and will experience the consequences of our possible failure to avert further climate change.32Year 2100 is often used as a reference year, see chapter 2 of the report, written by CICERO on commission from NIM. What is at stake is therefore whether we wrong those who are already alive, who in turn will have obligations to new generations in their own lifetime, in an unbroken overlapping chain of generations.33Stanczyk, “How quickly should the world reduce its Greenhouse Gas Emissions?” p. 20, Harvard Philosophy As the former UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment, John Knox, has written: “We do not need to look far to see the people whose future lives will be affected by our actions today. They are already here.”34A/HRC/37/58, paragraph 68.

(ii) The necessity of being able to assert one’s right

Another legal philosophical problem that is often raised regarding the status of future generations as rights-holders is that they will not be able to assert their rights – for the simple reason that they do not yet exist. Will theory within rights theory is based on the notion that there is a necessary link between rights and enforcement. It is nevertheless clear that there are several people who cannot enforce their rights but still have rights. The most obvious example is children. In addition, there are rights that one cannot renounce, even if one should want to, such as the right to life or the right not to be subjected to torture. These examples show that the existence of rights does not necessarily depend on whether the rights holder can or will enforce those rights.

The interest theory is an alternative rights theory that links the rights holder to whose interest is at stake. Such a theory could cover children and non-waivable rights – in addition to the interests of future generations. Even if the issue of enforcing the possible rights of future generations raises many questions, the fact that they themselves cannot assert their rights today is not a decisive objection. As we demonstrate in the chapter on Article 112 of the Constitution, their interests can be argued by proxy, see Section 1-4 of the Disputes Act.

(iii) Is it possible to have obligations to future generations?

A final challenge is often how interests that first materialise in the future can be relevant today. The objection seems to be that the future cannot affect the present in such a direct manner. Since rights and obligations are often regarded as two sides of the same coin, such an objection is difficult to understand.35See e.g. Eng, Rettsfilosofi (2007), pp. 145-148 and Smith, Konstitusjonelt demokrati (4th ed. 2019) p. 55. Even if they do not occur simultaneously, they are in a causal relationship with each other. From the perspective of the obligation, the injustice is committed by us in our present,36Stanczyk, p. 16. and the harmful consequences in terms of changing the climate balance in the atmosphere occur immediately.37See Chapter 2 of the report, written by CICERO on commission from NIM. The action is therefore completed on our part in the present, even if the adverse effects will extend into the future. That we must therefore take responsibility for the negative consequences of our actions, when we know that our actions harm fundamental interests of future generations, is accordingly entirely in line with the way that obligations are construed in other areas of law.38Lewis, “Human rights and intergenerational justice” in Ismangil, von der Schaaf and van Trost (eds.), Climate Change, Justice and Human Rights (Amnesty International Netherlands 2020), p. 82. The German Constitutional Court has recently held that the right to life and physical integrity in the German Constitition (article 2.2) places the State under an objective duty to protect future generations, even though they do not have subjective rights.

As with the identity problem mentioned above, we could also answer this temporal objection by referring to the fact that our actions and omissions now have direct consequences for those alive now.39Stanczyk, p. 21. The gap between the injustice being committed and the damage materialising is thereby reduced.

In the following, we will look at possible legal grounds for linking climate risks to States’ human rights obligations. We will first discuss Article 112 of the Constitution, then the ECHR and the UN conventions..

4. Section 112 of the Norwegian Constitution

Section 112 of the Norwegian Constitution recognises that everyone has a right to a healthy environment and an environment in which productivity and diversity are preserved. The provision further recognises that natural resources shall be utilised on the basis of a long-term perspective that safeguards these rights for posterity. To achieve this, Section 112 also stipulates that citizens have the right to information about the condition of the environment and about planned or implemented environmental interferences. In its last paragraph, the provision explicitly imposes a duty on the State to implement appropriate measures in order to achieve the aforementioned rights.

Section 112 played a central role in a 2020 climate lawsuit in which two environmental organisations contested the validity of a royal decree to grant ten petroleum exploration licenses in the southern and southeastern parts of the Barents Sea.1HR-2020-2472-P. NIM intervened with a written amicus curiae on general principles of law, available here. The Supreme Court of Norway, in its judgement provided a number of clarifications regarding the content of the provision.

With respect to the scope of application, the Supreme Court confirmed that Section 112 clearly offers protection in relation to climate change and greenhouse gas emissions (para. 147). Furthermore, the Court held that although Section 112 only applies to actions and effects occurring in Norway, it also encompasses exported emissions from Norwegian oil and gas, because Norwegian authorities can exert effective control over such emissions, and they undisputedly cause harm in Norway (paras. 149, 155 and 260).

A key point discussed in the case was determining whether – and if so, to what extent – Section 112 provides enforceable rights. The State argued that the provision exclusively sets out a non-justiciable positive duty for the State to take measures, that could be tried only through impeachement (para. 83). The Supreme Court disagreed. It held that the purpose of the provision could not be achieved if the State did not also have a negative duty to abstain from interferences (para. 143). For instance, the Court noted that Section 112 could give rise to a duty to deny production of located oil and gas “out of considerations for climate and the environment” (para. 222, 223). Furthermore, it would be “contrary to general principles of the rule of law” if the courts could not intervene against violations of the Constitution (para. 123). The State can thus be held accountable by citizens and organisations with regard to both the positive and the negative duty to preserve a healthy environment.

In matters decided by Parliament, however, the threshold for overruling is very high. Hence, decisions made by or with the consent of the Parliament, can only be overruled in the courts if there has been a serious breach of duty (para. 142). In these cases, Section 112 thus serves as a mere safety valve. To underpin the high threshold, the Court inter alia argued that fundamental environmental decisions necessitate broad political considerations and prioritisation, and that democratic values thus suggest that such decisions should be taken by elected bodies (para. 141).

As matters stood before the Court, it did not consider the implications of Section 112, first paragraph, second sentence, which states that the right to a healthy environment shall be safeguarded for future generations as well.2The exploration licences under review would not, in and of themselves, lead to significant greenhouse gas emissions. Several licenses had also been returned to the State by companies, empty-handed, because no oil and gas could be found. In cases concerning actual or foreseeable greenhouse gas emissions, it could be argued that unrestricted deference to political decision-making today, risks restricting political leeway in an intemporal sense, as rapid depletion of the finite carbon budget today would unilaterally and irreversibly offload a disproportionate burden to cut emissions on unrepresented younger and future generations, which in turn would threaten their future freedoms and potentially expose them to risks of severe climate-induced impairments of life, physical integrity and property.3See for example Neubauer et al. v. Germany, BVerfG, Order of March 24th 2021- 1 BvR 2656/18, para. 206 (German Constitutional Court), and References re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act 2021 SCC 11, para. 206 (Supreme Court of Canada).

In environmental questions which Parliament has not decided upon, the Court clarified that Section 112 can be invoked directly. The Court acknowledged that it could be difficult in practice to decide whether Parliament has taken a stance on an environmental problem (para. 139). This leaves the door open for interpretation, in climate cases in particular. It could reasonably be argued that where legislative assessments are based on presumptions that are scientificly outdated, Parliament has not decided on the issue and has not addressed the real problem at hand. Moreover, the Court did not address the threshold for judicial scrutiny with respect to admininstrative decisions in which Parliament has not been involved.

The procedural rights set out in Section 112, second paragraph, are under full judicial scrutiny. The Court further held that the level of judicial scrutiny increases in proportion to the severity of the consequences involved (para. 183). In light of the irreversible and potentially catastrophic effects of greenhouse gas emissions and run-away climate change above 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius, the Court’s reasoning implies high qualitative procedural requirements and intensified judicial scrutiny in cases concerning actual or foreseeable greenhouse gas emsisions. This appears to be in line with the procedural requirements posed by the Irish Supreme Court, the Dutch Supreme Court, the French Conseil d’État and the German Constitutional Court in cases on inadequate greenhouse gas emissions reduction policies.4Friends of the Irish Environment v. Ireland, [2020] IESC 49, para. 6.45 (requires specification “in some reasonable detail” of the measures to reduce emissions up to 2050); Urgenda v. the Netherlands, ECLI:NL:HR:2019:2007, para. 7.5.3 (the state had not “sufficiently substantiated” that the reduction of at least 25% by 2020 was an impossible or disproportionate burden); Commune de Grande-Synthe c. France, N° 427301, ECLI:FR:CECHR:2020:427301.20201119 (State must provide further justifications on the sufficiency of measures to reduce emissions by 40% by 2030); Neubauer et al. v. Germany, BVerfG, Order of March 24th 2021- 1 BvR 2656/18 (requires specification of emission reductions after 2030 to reach target of climate neutrality by 2050).

5. The European Convention on Human Rights

The right to life and well-being pursuant to Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR commits the State to protect citizens from real and imminent risks from environmental and natural disasters. This chapter discusses how this obligation relates to greenhouse gas emissions.

5.1. Introduction

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) does not explicitly contain the right to a clean and quiet environment, or the right to the preservation of the environment as such.1 Hatton v. United Kingdom [GC] (36022/97); Allen et al. v. United Kingdom (5591/07); Greenpeace E.V. et al. v. Germany (18215/06); Kyrtatos v. Greece (41666/98); Ivan Atanasov v. Bulgaria (12853/03); Dubetska et al. v. Ukraine (30499/03). The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which interprets the Convention with binding effect on State Parties, has nevertheless applied several of its provisions to environmental damage that has occurred or risks occurring in the future.2The ECtHR and the Commission have made nearly 300 decisions on environmental risks and harm, discussed here: https://www.coe.int/en/web/portal/concept-human-rights-for-the-planet The ECtHR has in particular interpreted environmental protection into Article 2 (the right to life) and Article 8 (the right to privacy, family life and a home), and occasionally into additional protocol no. 1 Article 1 (P1-1, the right to property). Applicants in climate cases communicated by the ECtHR have also invoked Article 3 (prohibition against inhuman and degrading treatment), Article 6 (access to court), Article 13 (right ot remedy), and Article 14 (prohibition against discrimination).

The question of whether the ECHR requires States to avert the risks that result from dangerous climate change can be examined in two ways. One way is to ask whether the State will be obliged to protect citizens from harm caused by past or inevitable climate change. This is a matter of adaptation to climate change. Based on ECtHR practice, the answer appears to be relatively clear. The State could be positively obliged under Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR to protect citizens from known risks of natural and environmental disasters and provide emergency relief after such incidents.3 Conc. ECHR Article 2: Budayeva et al. v. Russia (15339/02, 21166/02, 20058/02, 11673/02 and 15343/03); Öneryildiz v. Turkey [GC] (48939/99); Murillo Saldias et al. v. Spain (76973/01) presumably; Kolyadenko et al. v. Russia (17423/05, 20534/05, 20678/05); Özel et al. v. Turkey (14350/05, 15245/05, 16051/05); conc. ECHR Article 8: Guerra, et al. v. Italy [GC] (14967/89); Brincat et al. v. Malta (60908/11, 62110/11, 62129/11); Tãtar v. Romania (67021/01); Dubetska et al. v. Ukraine (30499/02); see also Dzemyuk v. Ukraine (42488/02). It could be a matter of protection under ECHR Protocol No. 1 Article 1 (P1-1): Öneryildiz v.Turkey; Dimitar Yordanov v. Bulgaria (3401/09). As the report focuses on mitigation, we will not discuss such an obligation to make adjustments in more detail here.

Another approach is to ask whether the State is committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avert dangerous or harmful climate change in the future.4Harmful effects of climate change are defined in Section 4 of the Climate Change Act, cf. Article 2(1)(a) of the Paris Agreement as global average temperature warming to more than the limit of tolerance of 1.5 to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius. This is unresolved. The ECtHR has not yet settled appeals about greenhouse gas emissions.The Supreme Court of the Netherlands has held that Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR, read in conjunction with Article 13, commit the Netherlands to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 25 per cent by the end of 2020 to protect its citizens from the real and imminent danger of dangerous climate change.5For more, see Chapter 9 of the report on climate-related legal cases based on human rights. The German Constitutional Court has held, with reference to Articles 2 and 8 of the ECHR, that the constitutional right to life, physical integrity and property obliges the State to protect against climate change by reducing emissions. The ECtHR has communicated and fast-tracked two cases on greenhouse gas emissions, pertaining inter alia to Articles 2 and 8.